CSSN Research Report 2021:3

Who’s Influencing Connecticut

Climate and Clean Energy Politics?

Five Questions

Policy Briefing

The Climate and Development Lab

Institute at Brown for Environment and Society

December 2021

About the authors

Trevor Culhane and Galen Hall are recent graduates

of Brown University and researchers in the Climate

and Development Lab at Brown University. J.

Timmons Roberts is Ittleson Professor of

Environmental Studies and Sociology in the Institute

at Brown for Environment and Society, and

Executive Director of the Climate Social Science

Network.

Produced by the Climate and

Development Lab

The Climate and Development Lab is a think tank at

Brown University informing a more just, equitable,

and effective global climate change policy. It is

housed at the Institute at Brown for Environment

and Society (see IBES.Brown.edu). The Institute at

Brown for Environment and Society (IBES)

supports research to understand the interactions

between natural, human and social systems. Our

teaching programs prepare future leaders to

envision and build a just and sustainable world.

About CSSN

This report is being released through the Climate

Social Science Network (CSSN.org), a global

network of scholars headquartered at the Institute

at Brown for Environment and Society, launched in

October, 2020. CSSN seeks to coordinate, conduct

and support peer-reviewed research into the

institutional and cultural dynamics of the political

conflict over climate change, and assist scholars in

outreach to policymakers and the public.

This report should be cited as:

Trevor Culhane, Galen Hall, and J. Timmons

Roberts. 2021. Who’s Influencing Connecticut

Climate and Clean Energy Politics? Five Questions.”

CSSN Research Report 2021:3. CSSN.org

Published by CSSN, December 2021

Trevor Culhane, Galen Hall, and J. Timmons Roberts

http://www.cssn.org/

Cover photo credit: Shutterstock, Real Window

Creative

Climate Social Science Network

Institute at Brown for Environment and Society

135 Waterman Street, Providence RI 02912 USA

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @ClimateSSN

More publications and information available at

CSSN.org

Acknowledgements

We appreciate support for this research from the

Barr Foundation. The opinions expressed in this

report are those of the authors and do not

necessarily reflect the views of the Barr Foundation.

We would also like to thank our interviewees and the

legislative staffers who provided testimony in

response to our requests. The support of the

Institute at Brown for Environment and Society has

been crucial to this project’s success.

Research Report: Who’s Influencing Connecticut Climate and Clean Energy Politics? Five Questions // 2

Executive Summary

Who is testifying at the Connecticut Capitol on climate and clean energy? What arguments are those

testifying against climate action using? What happens to clean energy bills? Who’s lobbying? What

economic sectors are most actively among those opposing climate solutions legislation in Connecticut

and what positions are they taking?

To address these questions, we analyzed publicly available written testimony on 48 bills that key

organizations and coalitions working on climate policy in Connecticut

1

saw as priority legislation from

2013-2020. In total, we analyzed 2,940 pieces of testimony, comprising 3,958 positions on legislation. We

carefully read and summarize 263 pieces of opposition testimony to capture dominant discourses against

climate solutions as they’ve been proposed in the state.

Electric and gas utilities spent over $24 million on lobbying over the eight years of this study, four times

that of renewable energy firms, and over eight times that of environmental organizations.

We find strong support for climate action in written testimony: 91.7% of the positions taken on climate and

clean energy bills supported priority climate legislation. This strong support spanned every year from

2013-2020 and nearly all issues. Large numbers of testifiers supported legislation to ban fracking waste in

Connecticut, facilitate shared solar energy, encourage electric vehicles, institute carbon pricing, create a

Green New Deal and limit new natural gas infrastructure. Individuals speaking on their own behalf made

up the largest segment of testimony, submitting over 3,000 positions on these bills - almost all in support

of climate solutions legislation.

Opposition to key environmental organizations’ positions on climate legislation was most frequently heard

from lobbyists and other staff from heating oil and alternative fuels companies, business associations,

and electric and gas utilities. In addition, the majority of positions taken in testimony from the utilities,

heating oils, business associations, auto, fossil fuel, and real estate sectors opposed key environmental

organizations’ positions on climate legislation. Eversource Energy and Avangrid/UIL Holdings submitted

over 20 positions each on a variety of issues. Two high-spending sectors identified in our lobbying analysis

were nearly completely absent from testimony: power generators and natural gas pipeline companies.

Rather than attacking climate science, testimony in the Connecticut legislature sought to delay or stop the

passage of individual climate and clean energy bills. We identified nine discourses frequently utilized in

opposing priority climate legislation. The natural gas industry and supporters argued that its expansion is

essential for the state economy. Climate bills were seen as disproportionately harmful to low-income

1

We selected these bills because key environmental organizations, primarily the Connecticut League of Conservation Voters

and Save the Sound/Connecticut Fund for the Environment, saw these as priority climate and clean energy bills. These

groups were selected in part because they consistently maintain publicly available lists of legislation related to climate and

clean energy. Full bill list available in Appendix.

Research Report: Who’s Influencing Connecticut Climate and Clean Energy Politics? Five Questions // 3

residents, and carbon pricing was dismissed as just another tax. Several industries expressed a strong

aversion to regulation and a preference for market-based incentives. Fossil fuel supporters argued that

renewables and EVs are being given unfair advantages. Connecticut was presented by representatives of

oil and gas distributors and the business association CBIA as too small to matter for the climate, and that

adoption of proposed policies would make the state appear anti-business. Finally, several industry

representatives argued that they and the state are already leaders on climate change.

We conclude with several recommendations:

Recommendations for the Legislature:

1: Evaluate and address utilities’ political influence.

2: Understand the new climate discourses.

3: Improve public voice and accountability at the Capitol.

4: Improve transparency and accountability.

Recommendations for Proponents:

1: Identifying opportunities for business support can advance policy.

2: Business lobbies may not be representing their members’ interests.

3: Broader coalitions can succeed.

Research Report: Who’s Influencing Connecticut Climate and Clean Energy Politics? Five Questions // 4

Contents

Executive Summary 3

Contents 5

Introduction and Background 6

Methods 9

Question 1: Who’s testifying at the capitol on climate change and clean energy? 11

Question 2: What issues do key groups support and oppose? 15

Question 3: Who’s spending most on lobbying in Connecticut? 19

Question 4: What happens to climate and clean energy legislation? 22

Question 5: What arguments are those testifying against climate action using? 24

Recommendations 33

Recommendations for the Legislature 33

Recommendations for Proponents 34

Acknowledgements 35

Appendix 36

Research Report: Who’s Influencing Connecticut Climate and Clean Energy Politics? Five Questions // 5

Introduction and Background

Gridlock in Washington over climate change and clean energy has now stretched over three decades. This

is in spite of worsening climate disasters and the steady accumulation of scientific studies documenting

that climate change is real, is urgent, and that humans are the cause. In this vacuum at the federal level,

states have become key battlegrounds for how the U.S. addresses this problem.

In the early years, Connecticut showed the way.

2

Connecticut jumped out in front in 1990 on climate

action, being the first state in the country to pass legislation requiring specific actions to reduce carbon

dioxide emissions. In 2001 the state joined a regional compact

3

with the goal of reducing emissions by

2010 and 2020, and including a long-term goal to reduce emissions to a level that would “eliminat[e] the

negative impacts of climate change”—a goal scientists suggested at the time would require 75 to 85

percent reductions by 2050. The state released a framework to meet those goals in 2002

4

, and published

in 2003 the nation’s first statewide greenhouse gas inventory. Nine months of consultations led to the

2004 Connecticut Stakeholder Recommendations, and that year Public Act 04-252 committed the state to

doing its share of the regional efforts.

5

2005 saw the release of the Connecticut Climate Change Action

Plan and the state’s joining of the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI), which focused on power

plant emissions.

In 2007 a bill required energy efficiency be the first choice in investments to meet electricity demand

(called Least Cost Procurement) and increased the state’s Renewable Portfolio Standard.

6

The

highest-profile step, however, was the drafting, passage, and signing of the Global Warming Solutions Act

(Public Act 08-98) in 2008, which set mandatory targets for the state to reduce its emissions by 2020 and

2050.

7

That same year, Governor Jodi Rell joined Governors Schwarzenegger, Sebelius and Corzine and 14

other signatories at Yale University to broadcast their Governors' Declaration on Climate Change. The goal

was fashioning a partnership between federal and state action on climate change. These early climate

actions in Connecticut were followed by more initiatives, departments, and plans, many focused on coping

with the rapidly increasing impacts of climate change on the state, including sea level rise, storm surges,

heat waves and flooding. Recent examples among these are the Governor’s Council on Climate Change

and the Comprehensive Energy Strategy issued by the Connecticut Department of Energy and

Environmental Protection (DEEP).

8

8

See https://portal.ct.gov/DEEP/Climate-Change/GC3/Governors-Council-on-Climate-Change.

7

The Global Warming Solutions Act (Public Act 08-98) set mandatory GHG reduction targets of 10% below 1990 levels by

2020 and 80% below 2001 levels by 2050.

6

An Act Concerning Electricity and Energy Efficiency (Public Act 07-242).

5

An Act Concerning Climate Change (Public Act 04-252).

4

Leading By Example Connecticut Collaborates to Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions,which establishes a framework for CT

to meet its GHG reduction goals.

3

New England Governors and Eastern Canadian Premiers (NEG/ECP) Climate Change Action Plan 2001. This was the first

international climate initiative aimed at collectively reducing GHG emissions.

2

The historical parts of this section draw heavily on “History of Climate Action in Connecticut” Yale Case #PH-16-01.

Published November 04, 2016.

Research Report: Who’s Influencing Connecticut Climate and Clean Energy Politics? Five Questions // 6

However the science of climate change has become far more dire, suggesting near complete phaseouts

of fossil fuels will be needed by 2050, or even 2040.

9

Just in the last year, legislatures in neighboring states

have passed a new generation of climate bills calling for the halving of emissions by 2030 and net zero

emissions by 2050. Connecticut has executive orders and bills calling for 45 percent reduction by 2030 but

still has an overall 2050 target of 80 percent reductions.

10

Advocates for climate action and clean energy in

the state have grown increasingly frustrated as bills have died in the legislature, and clean energy funds

levied on utility customers’ bills are sometimes diverted into the general fund to meet budget shortfalls.

11

Two recent examples are carbon pricing legislation and later initiatives inspired by the Green New Deal,

which despite large numbers of testifiers in favor, did not move out of committee.

To understand who exerts influence on climate policy in Connecticut, the Climate and Development Lab at

Brown University has systematically reviewed capitol lobbying and testimony records for and against

climate and energy legislation. We collected lists of priority legislation from top statewide climate

advocacy groups and then created databases of all testimony in legislative committees that were

considering priority legislation on climate change and clean energy, and lobbying expenditures and visits

to the Capitol and state agencies reported by industrial and environmental organizations on energy. This

briefing is based on systematic collection and analysis of 2,940 pieces of testimony on environmental

organizations’ priority bills from 2013 to 2020, and records of lobbying on “Energy” issues as reported to

the Connecticut Secretary of State over the period 2013-2020.

12

After initial research on campaign

contributions, we concluded that systematic work in understanding this area was not possible.

Our review resulted in answers to five broad questions: Who’s testifying at the Capitol on climate and clean

energy? What issues do key groups support and oppose--who’s lining up in opposition to priority climate

legislation, and why? Who’s spending most on lobbying? How many clean energy bills survived the

legislative process? And finally, what arguments are those testifying against proposed climate solutions

using? For three of these questions we offer numerical findings of broad patterns on testifying and

lobbying. On two others, we carefully read and summarize opposition testimony to capture dominant

discourses against climate action as it’s been proposed in the state.

Electric and gas utilities spent over $24 million on lobbying over the eight years of this study, four times

that of renewable energy firms, and over eight times that of environmental organizations.

We found that 91.7% of testimony supported priority climate bills, across every year and nearly all issues.

Individuals speaking on their own behalf made up the largest segment of testimony, submitting over 3,000

positions on these bills - almost all in support of climate solutions legislation. Large numbers of testifiers

supported legislation to ban fracking waste in Connecticut, facilitate shared solar energy, encourage

electric vehicles, institute carbon pricing, create a Green New Deal and limit new natural gas infrastructure.

12

We acknowledge the importance of nuclear energy in Connecticut, but have excluded it from the study to focus on

renewable energy and climate bills.

11

In 2018 $145 million was swept from the state’s clean energy fund to cover general budget shortfalls. Robert Walton,

“Connecticut Can Use Efficiency Funds to Cover Budget Shortfall, Court Rules,” Utility Dive, October 30, 2018.

10

SB7 was the 2018 Act Concerning Climate Change Planning and Resiliency. Office of Governor Ned Lamont. 2019.

Governor Lamont Signs Executive Order Strengthening Connecticut’s Efforts to Mitigate Climate Change. Press Release

September 3, 2019.

9

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 2018. Special Report on 1.5C Degrees of Warming. IPCC; National Climate

Assessment 2018. Washington, DC.

Research Report: Who’s Influencing Connecticut Climate and Clean Energy Politics? Five Questions // 7

Opposition to key environmental organizations’ positions on climate legislation was most frequently heard

from lobbyists and other staff from heating oil and alternative fuels companies, business associations,

and electric and gas utilities. In addition, the majority of positions taken in testimony from the utilities,

heating oils, business associations, auto, fossil fuel, and real estate sectors opposed environmentalists’

positions on key climate legislation. Eversource Energy and Avangrid/UIL Holdings submitted more

positions than any other firms, and the Connecticut Business and Industry Council (CBIA) and the CT

Petroleum Council were most frequently opposed. Two highly engaged sectors identified in our lobbying

analysis were nearly completely absent from testimony: power generators and natural gas pipeline

companies.

Rather than attacking climate science or denying the reality of the problem, opposition testimony in the

Connecticut legislature sought to delay or stop the passage of individual climate and clean energy bills.

We identified nine discourses frequently utilized in opposing priority climate legislation. The natural gas

industry and supporters argued that its expansion is essential for the state economy. Climate bills were

seen as disproportionately harmful to low-income residents, and carbon pricing was dismissed as just

another tax. Several industries expressed a strong aversion to regulation and a preference for

market-based incentives. Fossil fuel supporters argued that renewables and EVs are being given unfair

advantages. Connecticut was presented by representatives of oil and gas distributors and the business

association CBIA as too small to matter for the climate, and that adoption of proposed policies would

make the state appear anti-business. Finally, several industry representatives argued that they and the

state are already leaders on climate change. The report concludes with a series of recommendations.

Research Report: Who’s Influencing Connecticut Climate and Clean Energy Politics? Five Questions // 8

Methods

The bulk of research for this study was conducted from July 2020 to June 2021. The Connecticut Capitol

Complex was closed to visitors due to the COVID-19 pandemic for the entire research period and remains

closed at this writing.

13

Therefore we scraped full sets of written testimony and lobbying data from state

websites.

14

In the end we were able to remotely access all the information we needed, including

systematic collections of information about the introduction and fate of climate and clean energy

legislation in Connecticut, all lobbying records, and written testimony given on priority bills. To understand

some of the political context, we also conducted a series of ten interviews with experts, activists, and

former state officials, by video call. We describe each part of these methods, and then turn to our findings.

Legislation

We created three databases. One sought to track the fate of all climate and clean energy bills introduced in

the legislature from 2013 to 2020. For this stage, which informs our responses to Question 4, we used a

keyword search

15

and identified 354 bills related to climate and clean energy introduced. We used this list

of bills to chart the course of climate and clean energy legislation through the legislature, using LegiScan’s

bill tracking site.

Our testimony analysis focused on climate and clean energy bills that major climate-focused

organizations placed on their legislative priority lists. Focusing on these 48 bills allows us to capture the

key debates and analyze which groups support and oppose the efforts of key environmental

organizations. We collected lists online of bills these groups identified as priorities from 2013-2020

16

and

focused on bills on which the groups held a clear position.

Testimony Analysis

To collect testimony, we downloaded all pieces of written testimony available on the Connecticut

legislature’s website on 48 priority climate bills. From these, we removed comments and testimony from

state legislators, supplemental materials, and duplicates, leaving us with a total of 2,940 pieces of public

testimony on priority bills.

For each piece of testimony, we assessed who delivered it (and whether the testimony was given on

behalf of an organization), the bills upon which they testified, and the positions they took on each.

17

Organization names were standardized and grouped with a parent organization if applicable (for example,

AARP national and AARP Connecticut were both considered as testimony from “AARP”), and organizations

17

Testimony that expressed concerns about legislation was categorized as opposition.

16

We collected lists of bills from Connecticut League of Conservation Voters and Save the Sound from every year from

2013-2020. In addition, we collected priority bills as available from Sierra Club Connecticut, New England Clean Energy

Council, Connecticut Citizen Action Group, and Citizens Campaign for the Environment. Full list included in the Appendix.

15

The list of keywords is included in the Appendix. Our keyword search returned a large number of bills, from these we

manually excluded legislation not related to clean energy or climate change.

14

We downloaded recordings and transcripts of committee hearings and floor debates, but did not include them in our

analysis because we were not able to narrow testimony to priority climate bills.

13

Connecticut General Assembly website. “Please Note: The Capitol Complex is Currently Closed. Accessed 27 June, 2020.

https://www.cga.ct.gov Pazniokis, Mark. May 19, 2021. Connecticut is now open for business, but the state Capitol remains

closed to the public.

Research Report: Who’s Influencing Connecticut Climate and Clean Energy Politics? Five Questions // 9

organized around a clear industry interest were categorized under that industry. For example the Coalition

for Community Solar Access is organized largely by and for solar interests, so it was categorized as part

of the solar sector, even though it includes some environmental organizations. If an organization focused

on the environment, but emerged from a different kind of parent organization, they were coded with the

parent organization or type. For example, the United Church of Christ Northeast Environmental Justice

Center was categorized as a faith group, not an environmental group.

18

This grouping is intended to better

reflect the sector’s engagement with climate and energy issues.

Lobbying

To address Question 3: “Who’s spending most on lobbying in Connecticut?”, we created a third database

by downloading all publicly available lobbying records from the Connecticut State lobbying disclosure

website

19

for the four legislative sessions between 2013 and 2020. These records show the amount each

interest group spent on lobbying, who they paid to do the work of lobbying, and a set of “issues” on which

they lobbied for each legislative session. There was no “Climate change” option among these issues, so

we focused on those groups which recorded lobbying on “Energy” during at least one of the four sessions.

Over 400 interest groups recorded lobbying on “Energy” issues at least once over the four sessions we

studied. Some of these groups likely took at most a passing interest in climate legislation (e.g. Wine and

Spirits Wholesalers of CT). We therefore analyzed only those interest groups that either lobbied on

“Energy” during every session in which they were active, or testified on at least one environmental priority

bill. This filter selects for groups which more consistently engage in energy politics in Connecticut, leaving

us with 244 lobbying interest groups.

19

https://www.oseapps.ct.gov/NewLobbyist/PublicReports/PublicDashboard.aspx

18

Faith leaders were not categorized as speaking on behalf of an organization, unless they were a director of a particular

program and appeared to speak on that program’s behalf.

Research Report: Who’s Influencing Connecticut Climate and Clean Energy Politics? Five Questions // 10

Question 1: Who’s testifying at the capitol on

climate change and clean energy?

Who supports and opposes climate action in Connecticut? Which economic sectors have representatives

testify in support of climate and clean energy policies, and which sectors tend to oppose them? To

address these questions, we analyzed publicly available written testimony on 48 bills that key

climate-focused organizations

20

saw as climate and energy priorities from 2013-2020. In total, we

analyzed 2,940 pieces of testimony on these 48 bills, comprising 3,958 positions on legislation.

21

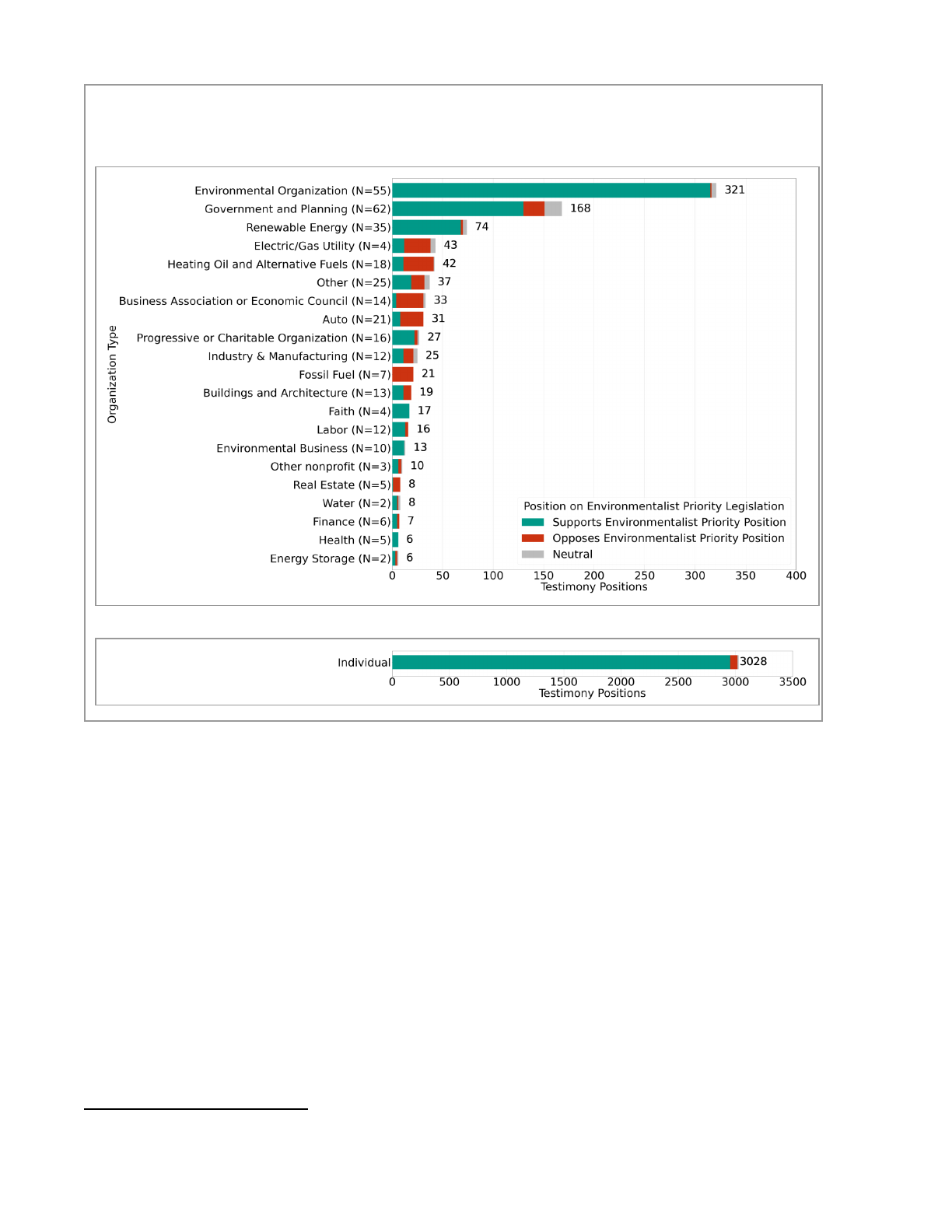

Finding 1.1: There is strong support for climate action in written testimony. 91.7% of the positions taken

on climate and clean energy bills supported priority climate legislation. There was strong support every

year from 2013-2020 and across different sub-issues. A majority of testifiers supported priority climate

legislation on 45 of the 48 bills we examined.

22

Finding 1.2: Individuals speaking on their own behalf made up the largest segment of testimony,

submitting over 3,000 positions on these bills - almost all in support of priority climate legislation

(Figure 1b). 97.5% of individuals’ positions on bills supported priority climate legislation. Opposition to

priority climate legislation from individuals was primarily limited to a carbon pricing bill (2018 HB-5363): 58

pieces of testimony were submitted against it, many of which were short emails arguing that carbon taxes

would be economically damaging to Connecticut (see Question 5).

23

Testimony is the only formal process

whereby the legislature invites public input on legislation, and this testimony demonstrates strong public

support for climate and clean energy policies.

Finding 1.3: Environmental organizations, government and planning groups, and renewable energy

companies are the most frequent testifiers in support of priority climate legislation (Figure 1a).

Progressive and charitable organizations, environmental businesses, faith groups, and labor groups also

give most of their testimony in favor of priority climate legislation, but do not appear frequently to support

priority climate bills. A majority of faith group testimony was for the fracking waste ban bill (Figure 2).

23

Other than carbon pricing, only six pieces of written testimony were submitted against major climate-focused

organizations by individuals on all other bills: four employees of car dealerships submitted testimony against direct sales of

electric vehicles, one person submitted testimony against the Green New Deal, and one individual in support of natural gas

pipelines.

22

For the other three bills, each with five or fewer pieces of testimony, two had equal support and opposition, and one had

more opposition than support (three positions opposing major climate-focused organizations, two supporting major

climate-focused organizations).

21

3,948 positions (99.7% of analyzed positions) were on bills key environmental groups supported, while 10 positions in

testimony were on 2 bills that key environmental groups opposed.

20

We selected these bills because key climate-focused organizations, primarily the Connecticut League of Conservation

Voters and Save the Sound/Connecticut Fund for the Environment, saw these as priority climate and clean energy bills.

These groups consistently maintain publicly available lists of legislation related to climate and clean energy.

Research Report: Who’s Influencing Connecticut Climate and Clean Energy Politics? Five Questions // 11

Testimony Positions For and Against Leading Environmental Organizations

a) Organization Testimony (N=number of organizations)

b) Individuals

Figure 1: Written testimony on key climate and energy bills 2013-2020, Connecticut.

Finding 1.4: Opposition to key climate legislation is concentrated in several sectors: Electric/Gas

Utilities, Heating Oil and Alternative Fuels, Business Association or Economic Councils, the Auto

industry, Fossil Fuels, and Real Estate. Of these, the utility, business association, and fossil fuel sectors

had the most engaged individual organizations: AVANGRID/UIL Holdings, CT Business and Industry

Association, CT Petroleum Council, and Eversource Energy submitted more than 10 positions each in

opposition to priority climate positions, more than double any other actor (Table 1b). In contrast, the auto

and heating oils sectors were composed of many smaller companies and organizations, each of which

submitted few pieces of testimony. Arguments made against climate action are outlined in Question 5.

Two of the biggest lobbying spenders on Energy - Spectra Energy Transmission II LLC and MMCT

Ventures LLC - did not submit any written testimony, and testimony from natural gas pipeline companies

and power generators was rare.

24

24

Lobbying analysis is explained in Question 3.

Research Report: Who’s Influencing Connecticut Climate and Clean Energy Politics? Five Questions // 12

Finding 1.5: The main support for priority climate legislation comes from better-resourced

environmental organizations and government/quasi-government agencies that focus on environmental

issues (Table 1a). Save the Sound and Sierra Club both testified over 30 times, while Environment

Connecticut, CT League of Conservation Voters, CT Citizen Action Group and Acadia Center all testified

over 15 times.

Research Report: Who’s Influencing Connecticut Climate and Clean Energy Politics? Five Questions // 13

Table 1: Top testifiers for and against priority climate legislation, Connecticut, 2013-2020.

(a) Groups taking ten public positions or more in support of leading environmental organizations on

climate bills.

Organization

Stance on Priority Climate Bills

Supports

Opposes

Neutral

Save the Sound

39

Sierra Club

33

1

1

Environment CT

22

CT League of Conservation Voters

21

CT Citizen Action Group

19

Acadia Center

16

CT Dept. of Energy & Environmental Protection

14

3

3

CT Green Bank

14

Citizens Campaign for the Environment

14

Clean Water Action

14

Ashford Clean Energy Task Force

12

CT Roundtable on Climate and Jobs

10

Environment and Human Health

10

Office of Consumer Counsel

10

3

3

(b) Opposition groups taking three public positions or more in opposition to leading environmental

organizations on climate bills.

Organization

Stance on Priority Climate Bills

Opposes

Supports

Neutral

AVANGRID/UIL Holdings Corporation

14

5

1

CT Business and Industry Association

13

3

1

CT Petroleum Council

13

Eversource Energy

12

5

4

CT Home Builders and Remodelers Assn.

5

1

Daniels Energy

5

CT Realtors

4

CT Energy Marketers Association

4

5

Santa Energy

3

Office of Consumer Counsel

3

10

3

Middlesex County Chamber of Commerce

3

CT Industrial Energy Consumers

3

CT Dept. of Energy & Environmental Protection

3

14

3

CT Conference of Municipalities

3

4

4

AARP

3

4

Research Report: Who’s Influencing Connecticut Climate and Clean Energy Politics? Five Questions // 14

Question 2: What issues do key groups support

and oppose?

We identified 19 issues among the 48 priority climate bills, such as banning the dumping of waste from

hydraulic fracturing, solar, wind, carbon pricing and the Green New Deal.

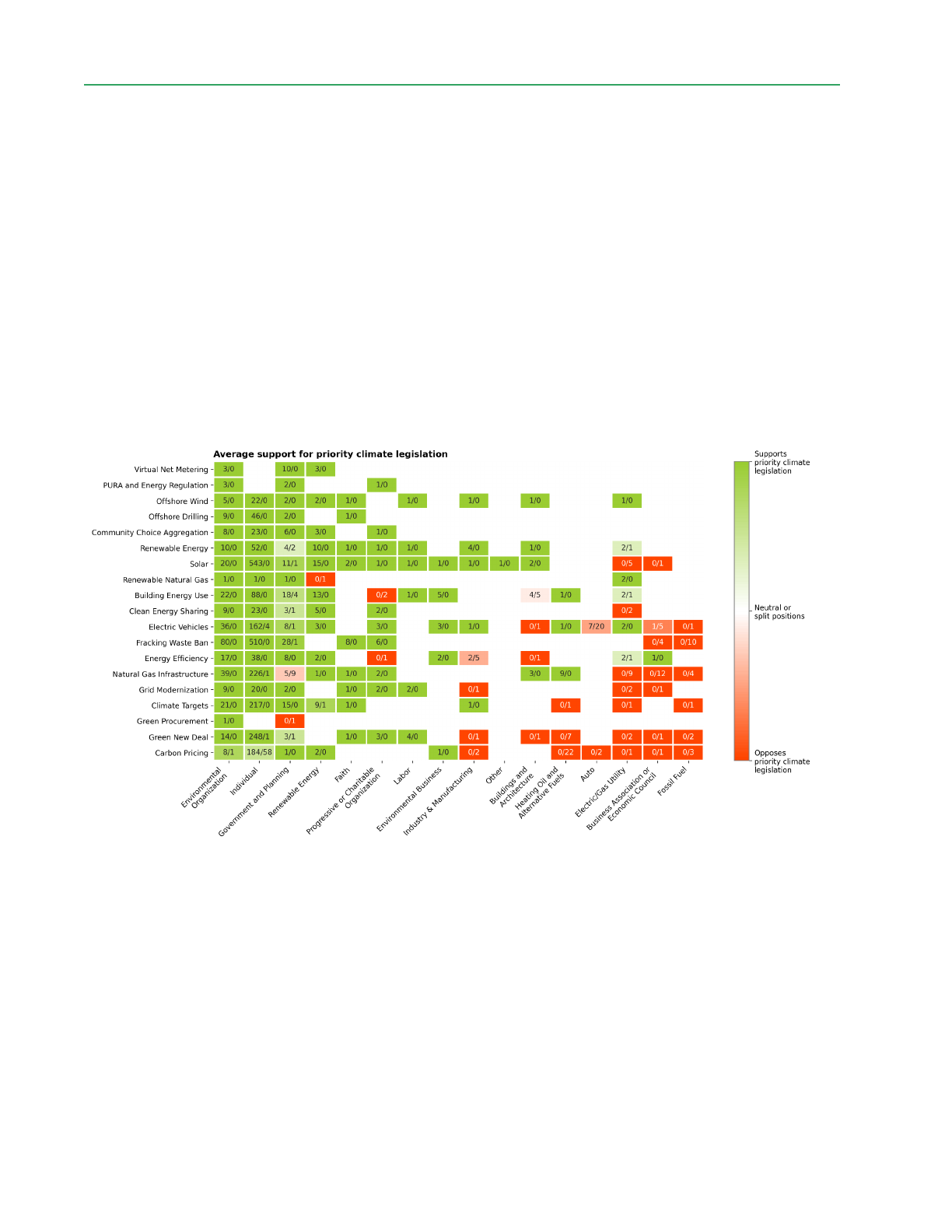

Finding 2.1: A majority of testifiers supported priority climate legislation (Figure 2). Bills related to

natural gas infrastructure, specifically regulating fracking waste and natural gas pipelines, received the

most testimony of the bills we examined, followed by bills related to solar energy, electric vehicles, and the

Green New Deal. The most contested issue area was carbon pricing (see Question 5).

Figure 2. Summed testimony positions on bills in each issue space from organizations in each sector. The

figure includes the top 15 sectors by total testimony given, sorted from the most favorable to leading

environmental groups’ positions on priority climate legislation (left) to the least favorable (right).

Annotations in each cell show the amount of testimony in support on the left and the amount in

opposition on the right. Where no organization in a sector testified in support or opposition to priority

legislation on a given issue the cell is left blank.

Finding 2.2: Solar legislation had strong advocate support and key utility opposition. Solar policies,

particularly policies to enable shared solar developments, saw strong support among environmental

Research Report: Who’s Influencing Connecticut Climate and Clean Energy Politics? Five Questions // 15

groups and their allies. These bills were among the most testified upon bills in our study, with 597

individual testifiers in support.

Six pieces of testimony were against solar bills. The utility industry testified strongly against legislation to

expand solar energy, particularly against two policies. The first, called net metering, allows home- and

business-owners to sell extra electricity produced by their solar panels back to the grid, and only be billed

for the net amount of extra energy needed from the grid. Second, utilities opposed shared clean energy

programs, which would allow energy consumers to subscribe to a local shared renewable energy project

and receive a credit on their utility bill for the power produced.

25

Eversource’s Stephen Gibelli testified on

2015 SB-928 that "As such we applaud the goals of this bill to further the development of renewable

resources within our state.[...] We are concerned that bills such as these will shift costs to

non-participating customers, which may particularly impact our low income customers.."

26

While environmental groups, labor, and many municipalities all supported solar energy and testified for

solar energy policies, specific proposals related to the method of solar development were contested.

Municipalities contested tax exemptions for certain new solar developments, some more

conservation-focused environmental groups worked to ensure solar siting would not jeopardize land

protections, and labor groups (along with environmental groups) called for prevailing wage standards for

new solar developments. These efforts were contested by some members of the Connecticut solar

industry, who see such attempts as barriers to their growth.

27

Finding 2.3: Offshore Wind bills had nearly universal support. In contrast to solar legislation, the priority

offshore wind bill included in our study, 2019 HB-7156, An Act Concerning The Procurement Of Energy

Derived From Offshore Wind, saw nearly universal support in testimony. Environmental groups, along with

labor, utility, faith, and renewable energy representatives all supported the project, although in relatively

small numbers. There was no written opposition testimony from business councils, the fossil fuel industry,

or most other sectors.

Eversource Energy, who is a leading developer of offshore wind energy in the Northeast, wrote,

“Eversource appreciates the leadership of Governor Lamont and the Connecticut legislature to take a

critical step in achieving Connecticut's clean energy economy. We fully support the State's efforts to

increase its offshore wind procurement authority. Offshore wind holds the promise to provide significant

quantities of affordable, carbon-free energy while supporting hundreds of new jobs in Connecticut and

throughout the Northeast.”

The only group to submit testimony against the bill was the New England Power Generators’ Association

(NEPGA), whose members represent approximately 26,000 megawatts of generating capacity in New

England. They wrote in testimony: “NEPGA opposes SB 875 and HB 7156 because both bills would

increase out-of-market procurements of offshore wind resources, which would further displace

27

Authors’ interview with solar industry representative.

26

This opposition is consistent with research on the utility industry’s efforts in neighboring states, see our recent report on

Massachusetts and see Short Circuiting Policy: Interest Groups and the Battle Over Clean Energy and Climate Policy in the

American States, by Leah Stokes (2020).

25

Environmental groups focused on the opportunities these programs would provide for solar energy developments in

particular.

Research Report: Who’s Influencing Connecticut Climate and Clean Energy Politics? Five Questions // 16

cost-effective generation in the wholesale market place, and, over time, expose consumers to the risks of

long-term contracts to support resources needed for reliability. Instead, if, as some proponents have

stated, this is a proposal intended to help Connecticut meet its Global Warming Solutions Act mandates,

NEPGA suggests the better, more competitive way would be to work with states in New England to set a

meaningful price on carbon dioxide emissions for electricity and other sectors of the economy –

particularly transportation.”

Finding 2.4: Bills restricting natural gas were highly contested and created unusual alignments. Bills

requiring better methane leakage efforts and restricting natural gas infrastructure brought support from

environmental organizations, the public, and delivered fuel companies. They were strongly resisted by

utilities, business councils and some municipal groups.

Environmental groups and individuals testified in favor of restrictions on natural gas expansion and

methane leaks, with 283 positions submitted in support of priority climate legislation out of 328 total

positions on natural gas infrastructure bills. They were joined by several government groups, along with

the heating oil and alternative fuels industry. In contrast, a broad array of groups, including business

councils, utilities, the fossil fuel industry, and other municipal and government groups, all testified in favor

of expanding natural gas infrastructure or insulating the industry from further regulation. Their arguments

are explored further in Question 5. Natural gas was a key issue for utilities, with Eversource and Avangrid

both testifying against bills to limit pipeline construction and reduce methane leaks in the state.

28

While heating oil and alternative fuel companies often opposed climate advocates on other issues, the two

sectors did align on natural gas infrastructure. Expanding natural gas infrastructure, particularly to rural

areas that don’t currently have it, would take customers away from heating oils and alternative fuels

companies. Heating oil companies testified for stronger policies regulating natural gas pipeline leaks.

Connecticut Energy Marketers Association (CEMA)’s President, Christian Herb, stated “The “no leak” policy

that applies to the 600 local family owned home heating oil/Bioheat® dealers along with the 1,400

gasoline station owners does not apply to Yankee Gas/Eversource and Southern Connecticut Gas and

Connecticut Natural Gas/Avangrid. This double standard is harmful to the environment and independently

owned businesses” (2020 HB-5350). On the other side, Steve Guveyan of the Connecticut Petroleum

Council argued on a major pipeline bill that "The bill […] discriminates sharply against natural gas by

eliminating interstate gas pipelines from the future energy mix. Barring pipeline expansion will inhibit

future economic growth [...] An all-of-the-above approach to energy supply works best” (2018 SB-332).

Finding 2.5: Carbon pricing was the most contested issue. An Act Establishing a Carbon Price for Fossil

Fuels Sold in Connecticut (2018 HB-5363), was the most contested bill in our study, with 97 positions from

testimony in opposition and 197 positions in support. The bill saw significant support from environmental

organizations and individuals, but little testimony from municipalities, renewable energy companies, and

other sectors who tend to support other climate bills.

29

29

The Sierra Club submitted testimony that they would not support the bill unless it were amended, writing that, “to earn our

support, the Sierra Club requests that HB-5363 be amended to: 1) Invest at least 50 percent of the revenues in opportunities

to reduce pollution, increase access to the benefits of clean energy, and help workers and communities move beyond dirty

energy, with a minimum level for overburdened and underserved communities. 2) Provide rebates only for residents in the

28

Eversource Energy is co-leader of the Consortium to Fight Electrification, whose mission is to “create effective,

customizable marketing materials to fight the electrification/anti-natural gas movement." See Leaked docs: Gas industry

secretly fights electrification, Benjamin Storrow, E&E News (2021).

Research Report: Who’s Influencing Connecticut Climate and Clean Energy Politics? Five Questions // 17

The 2018 hearing on carbon pricing legislation included 14 positions in written testimony from small

heating oil delivery companies. David Sousa, who declared in his written testimony on 2018 HB-5363 that

his family ran a heating oil company, said "This tax is a street sign that says, turn around if you are thinking

of moving to Connecticut. […] Meanwhile certain fuels like coal and oil are being vilified" (2018 HB-5363).

Jamie Lohr, President of Guardian Fuel and Energy testified that "In my company, and countless other

family heating oil dealerships across the state, we work to help families make good decisions in budgeting

for their fuel, and in making their homes energy efficient as possible."

30

CT Petroleum Council argued that “In effect, this is an income-redistribution program." "[I]t clearly picks

winners and losers." "Instead, let CAFÉ standards, appliance standards and Renewable Portfolio Standards

(RPS) lead the way so there aren't overlapping regulatory requirements for greenhouse gas emissions"

(2018 HB-5363).

Finding 2.6: Opposition to electric vehicle bills focused on dealerships. 33 pieces of testimony on

priority climate legislation opposed legislation to promote electric vehicles, in contrast to 470 pieces of

testimony in support. Most of the opposition came from the auto industry, whose testimony on priority

climate legislation from 2013-2020 focused on opposing policies to allow the direct sale of electric

vehicles, the sales model proposed by Tesla over several years. In this way, auto industry testimony was

not explicitly against a climate solution, but against how it was to be marketed. Most of this testimony

came from individual dealerships, who testified against the direct sales model used by Tesla, which drops

cars off at purchasers’ homes. Auto dealerships see the direct sales model as a threat to their industry,

stating that allowing this model for electric vehicles would be a slippery slope towards eliminating the

dealership business in Connecticut. A series of dealers elaborated about the benefits they bring to

communities and customers. The Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers argued that "As drafted, the bill

would seemingly only allow Tesla to sell outside the franchise system governing every other manufacturer.

But what will the legislature do when the next company decides to enter the U.S. market to sell electric

vehicles? There are 23 major automakers that sell around the world, but not in the U.S." (2019 HB-7142). A

few dealers argued that their dealerships do sell electric vehicles, and that they would soon be selling

more.

30

Erin Santa Mercede made many of the same points that were made in the letters sent by other heating oil companies:

"Half the homes in the state are heated with fuel oil. A 16.55 cents/gall tax on home heating oil would cost homeowners

$166 per year individually, or over $72 million per year in aggregate. And that's just in year one [...] The tax is a "feel good" tax

that won't affect climate change. According to a U.S. News & World Report article, even if the U.S. completely stopped

emitting all CO2, it would reduce world temperatures by only 0.08 degrees C by the year 2050." (2018 HB-5363)

lower income quintiles and small businesses, to ensure those who are most disadvantaged by our current energy and

economic systems are better off.”

Research Report: Who’s Influencing Connecticut Climate and Clean Energy Politics? Five Questions // 18

Question 3: Who’s spending most on lobbying

in Connecticut?

Lobbying disclosures give a sense of the resources that different interest groups draw upon in their

attempts to influence climate legislation. Because lobbying disclosures in Connecticut only list interest

groups’ expenditures, the lobbyists they hired, and a set of “issues” on which they lobbied during each

two-year session, we can say little about the details involved in lobbying activities in Connecticut.

31

Nonetheless, these records show important disparities in the amount of resources different interest

groups can draw on to influence the legislature.

As mentioned in the methods section, we start with over 400 interest groups who recorded lobbying on

“Energy” issues at least once over the four sessions we studied. Selecting only groups which engage

consistently (all years) or publicly (through testimony) on energy or climate change leaves us with 244

lobbying interest groups.

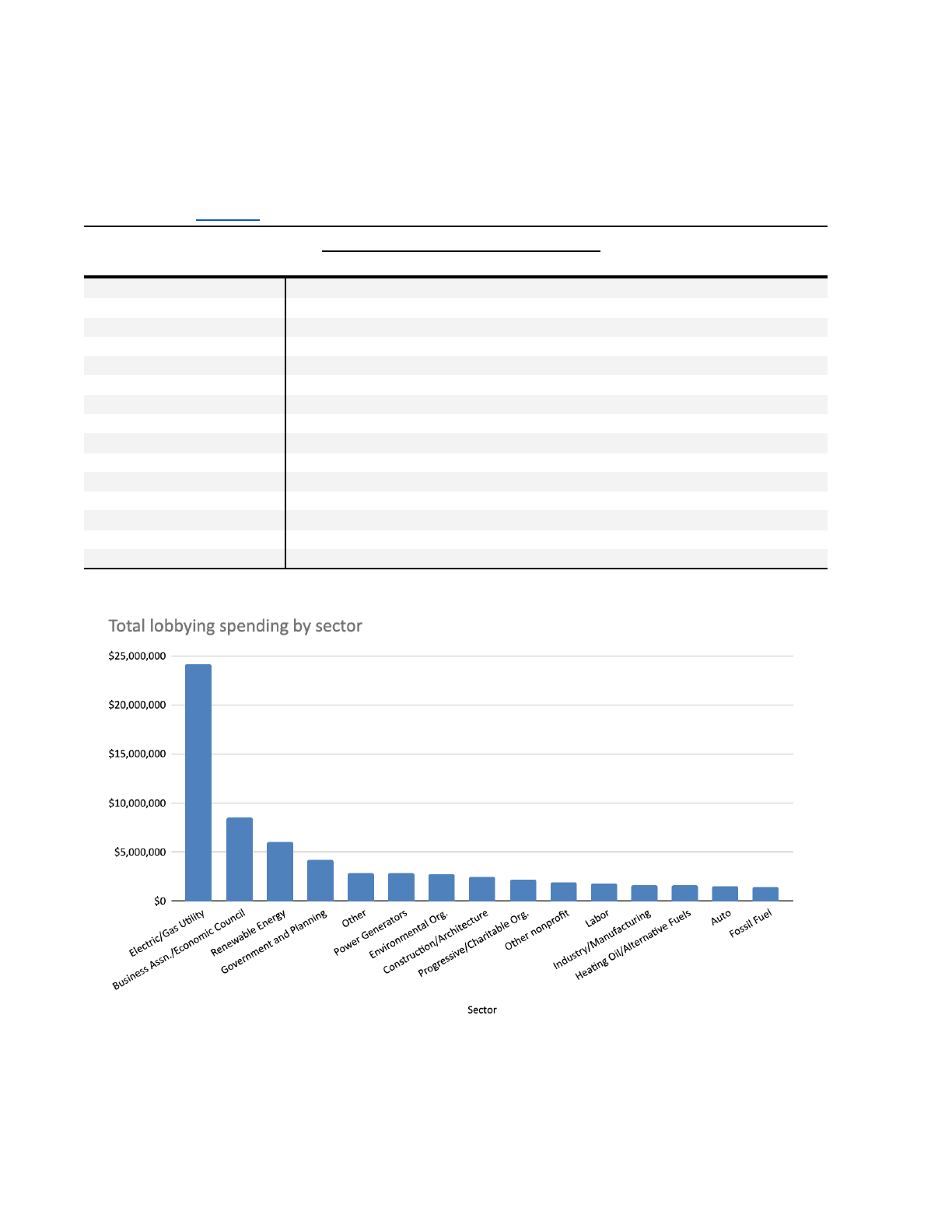

Finding 3.1: Lobbying spending is highly unequal

The distribution of lobbying budgets within this group skews heavily towards a set of high-spending

interests (Table 2). As is often the case, nonprofits comprise a large fraction of climate and clean

energy advocates in Connecticut, but they face a stiff spending imbalance in the arena of lobbying.

The median environmental organization spent $76,000 on lobbying over the eight-year period. At least

40 renewable energy firms also lobby actively in Connecticut, but most of them have small budgets —

the median is $39,608 over eight years. These figures compare to $181,000 over the same period

from the median power generation firm and $320,000 from the median electric or gas utility. Based

on these records, the median environmental organization or renewables firm has between one half

and one fourth of the lobbying budget of the median fossil-powered generation firm or electric and

gas utility company.

These differences are even more stark among the top-spending interest groups in each sector.

Among environmental organizations, Consumers for Sensible Energy (an anti-pipeline advocacy

group with undisclosed donors and a focus on elite lobbying

32

) spent $1.1 million on lobbying over

this period — almost double the next-highest environmental group, Save the Sound. NRG Energy, the

top renewables firm, spent only slightly more ($1.6 million). Conversely, the top utility, Eversource,

spent nearly $6.8 million on lobbying, and the Connecticut Business and Industry Association (CBIA)

spent nearly $4.6 million. Both were among the top five most consistent testifiers against priority

climate legislation. Further, the top ten interest groups active in the climate and energy space in

32

Bruce Mohl, “Who’s behind Consumer Energy Group?,” CommonWealth Magazine, December 4, 2017.

31

We cannot identify all groups who lobbied on climate legislation; the closest this data allows is to find groups which

registered having lobbied on “Energy”. Unlike in Massachusetts, where lobbying data is far more detailed, we have to rely

entirely on testimony to describe the detailed policy preferences of these interest groups.

Research Report: Who’s Influencing Connecticut Climate and Clean Energy Politics? Five Questions // 19

Connecticut (Table 3) include utilities, generation companies, and other industrial interests, but no

renewables or environmental groups.

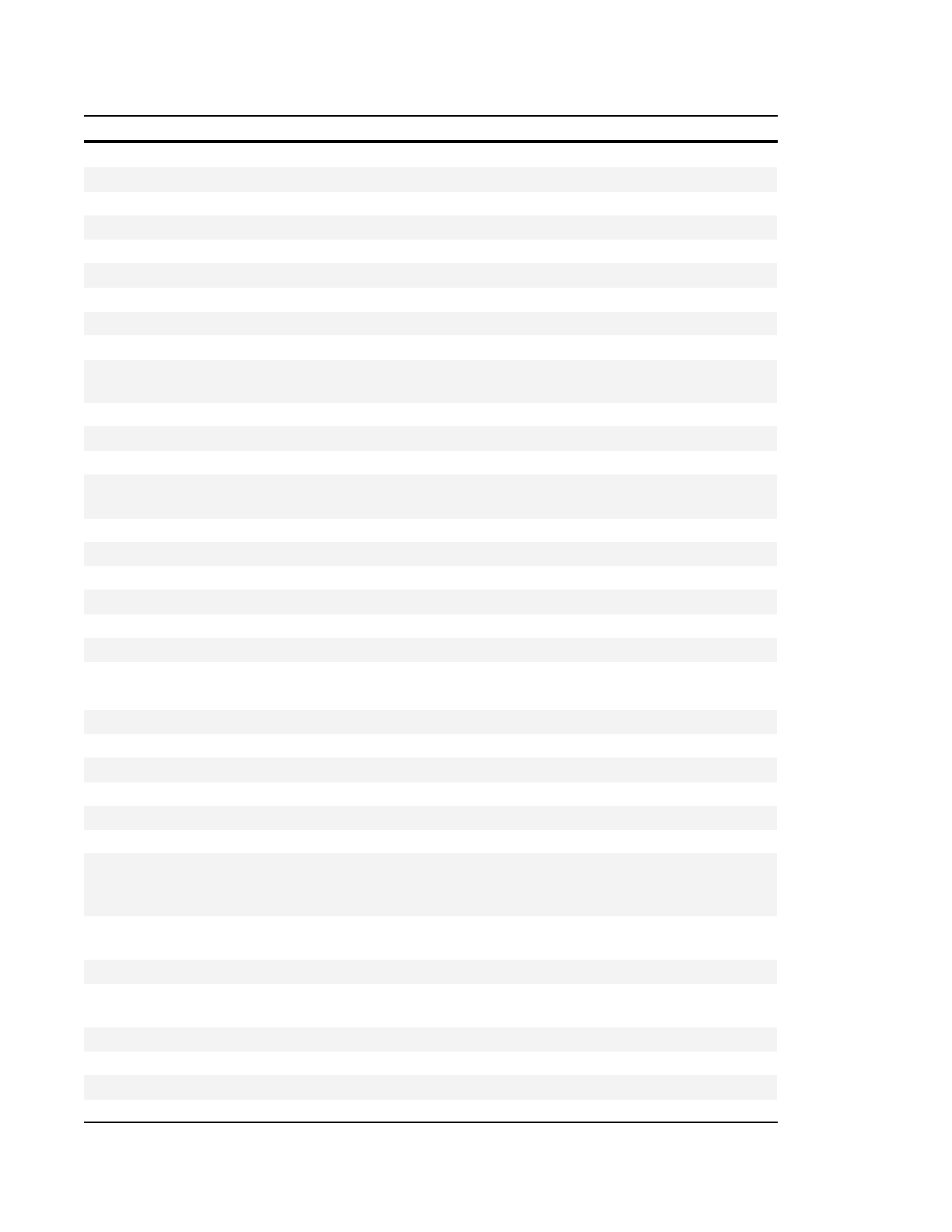

Table 2: Lobbying by sector. The top 15 sectors by total lobbying spending over the period are

shown. “Highest Spender” identifies the organization with the greatest total spending over the period

in each sector. (Source)

Sector

N

Lobbying spending, 2013-2020

Highest Spender

Median

Total

Highest

Electric/Gas Utility

25

$291,872

$24,206,899

$6,776,686

Eversource

Business Assn./Council

17

$153,533

$8,556,964

$4,575,350

CT Business & Industry Assn.

Renewable Energy

40

$39,608

$6,022,834

$1,587,587

NRG Energy Inc.

Government and Planning

9

$236,000

$4,167,360

$1,773,945

CT Conference of Municipalities

Other

12

$17,998

$2,915,432

$2,666,296

MMCT Ventures Inc.

Power Generators

15

$154,288

$2,852,172

$816,342

CPV Towantic Inc.

Environmental Org.

14

$72,463

$2,761,036

$1,130,749

Consumers for Sensible Energy

Construction/Architecture

4

$385,715

$2,494,406

$1,718,976

CT Construction Ind. Assn.

Progressive/Charitable Org.

14

$133,093

$2,244,458

$519,851

CT Legal Services Inc.

Other nonprofit

1

$1,884,814

$1,884,814

$1,884,814

AARP

Labor

6

$227,994

$1,818,069

$858,236

Operating Engineers Union

Industry/Manufacturing

13

$39,502

$1,627,380

$498,593

CT Ind. Energy Consumers

Heating Oil/Alt. Fuels

9

$78,951

$1,611,655

$635,788

Covanta Energy LLC

Auto

4

$292,676

$1,547,219

$961,648

Tesla Motors Inc.

Fossil Fuel

5

$108,060

$1,439,191

$743,650

CT Petroleum Council

Figure 3: Total lobbying spending by sector from 2013-2020.

Lobbying budgets only convey one part of the strategic landscape surrounding energy policy. Many

groups -- especially environmental organizations -- do more than just lobby; they run public education

Research Report: Who’s Influencing Connecticut Climate and Clean Energy Politics? Five Questions // 20

and pressure campaigns, protests and acts of civil disobedience, mutual aid, and use other tactics to

engage with the public as much as, or more than, they engage political elites. Nonetheless, in the

arena of elite lobbying we have seen that interest groups advancing progressive climate policies likely

face systemic disadvantages.

Table 3: Top ten lobbying spending groups in Connecticut, 2013-2020. Includes only interest

groups which registered lobbying on energy during every active session. Organizations sorted by

average yearly budget.

(Source)

Principal

2013-2014

2015-2016

2017-2018

2019-2020

Average

Total

Eversource

$1,572,710

$1,598,955

$1,864,802

$1,740,220

$1,694,172

$6,776,686

CT Business and Industry

Association

$1,091,215

$1,280,196

$1,407,271

$796,669

$1,143,838

$4,575,350

Spectra Energy Transmission II

LLC

$612,857

$2,399,006

$722,216

$244,605

$994,671

$3,978,685

Move CT Forward

$973,651

$986,126

$979,889

$1,959,778

Dominion Energy

$919,104

$878,241

$946,401

$875,370

$904,779

$3,619,116

MMCT Ventures LLC

$421,091

$1,271,748

$973,458

$888,765

$2,666,296

Avangrid/UIL Holdings Corp.

$878,445

$778,839

$579,448

$614,949

$712,920

$2,851,681

AARP

$798,875

$573,669

$262,909

$249,360

$471,204

$1,884,814

CT Conference of Municipalities

$358,138

$412,989

$526,671

$476,147

$443,486

$1,773,945

The CT Construction Industries

Association

$308,136

$372,712

$511,094

$527,033

$429,744

$1,718,976

Total

$6,539,481

$8,715,698

$9,066,212

$7,483,937

$8,663,468

$31,805,328

Research Report: Who’s Influencing Connecticut Climate and Clean Energy Politics? Five Questions // 21

Question 4: What happens to climate and clean

energy legislation?

There are numerous steps a bill must go through to become a law in Connecticut.

33

At multiple

stages throughout the process, a bill may be killed, amended, merged with other bills, or rewritten

entirely. While we will not review the entire process for how a bill becomes a law here, there are

several key decision points worth noting. First, the bill must be introduced, either by the governor, a

committee, or an individual legislator (individual legislators are only able to introduce bills in

odd-numbered years). Introduced bills are then referred to a committee; the committee then decides

whether to hold a hearing for a bill, where public testimony can be heard. After a hearing, bills may be

screened - sometimes several times - where the Legislative Commissioners Office writes the bill into

a draft law. For bills introduced by individual legislators, the committee can “vote to draft” the bill -

this step is necessary for the bill to move forward.

The committee will then pass the bill forward or hold the bill - effectively killing the bill. Bills may also

be sent to other committees. If the bill makes it out of committee, it is studied by the Offices of

Legislative Research and Fiscal Analysis, which creates a report about the bill’s impacts. If the bill will

cost the state money, the bill may move to the Appropriations Committee. After negotiations, in which

the bill can be amended or rewritten multiple times, the bill can move to a floor vote in either the

House or the Senate (depending on where the bill originated). If the bill passes each chamber in

identical form, it moves to the Governor’s Office. The governor can then sign the bill into law, or veto it

- the legislature may override a governor’s veto with a two-thirds majority vote of both chambers.

33

Shaiken, Ben. “HOW A BILL BECOMES A LAW Connecticut Edition!” Prepared by Ben Shaiken, Chair of Mansfield

Democratic Town Committee. Accessed 28 June 2021.

Research Report: Who’s Influencing Connecticut Climate and Clean Energy Politics? Five Questions // 22

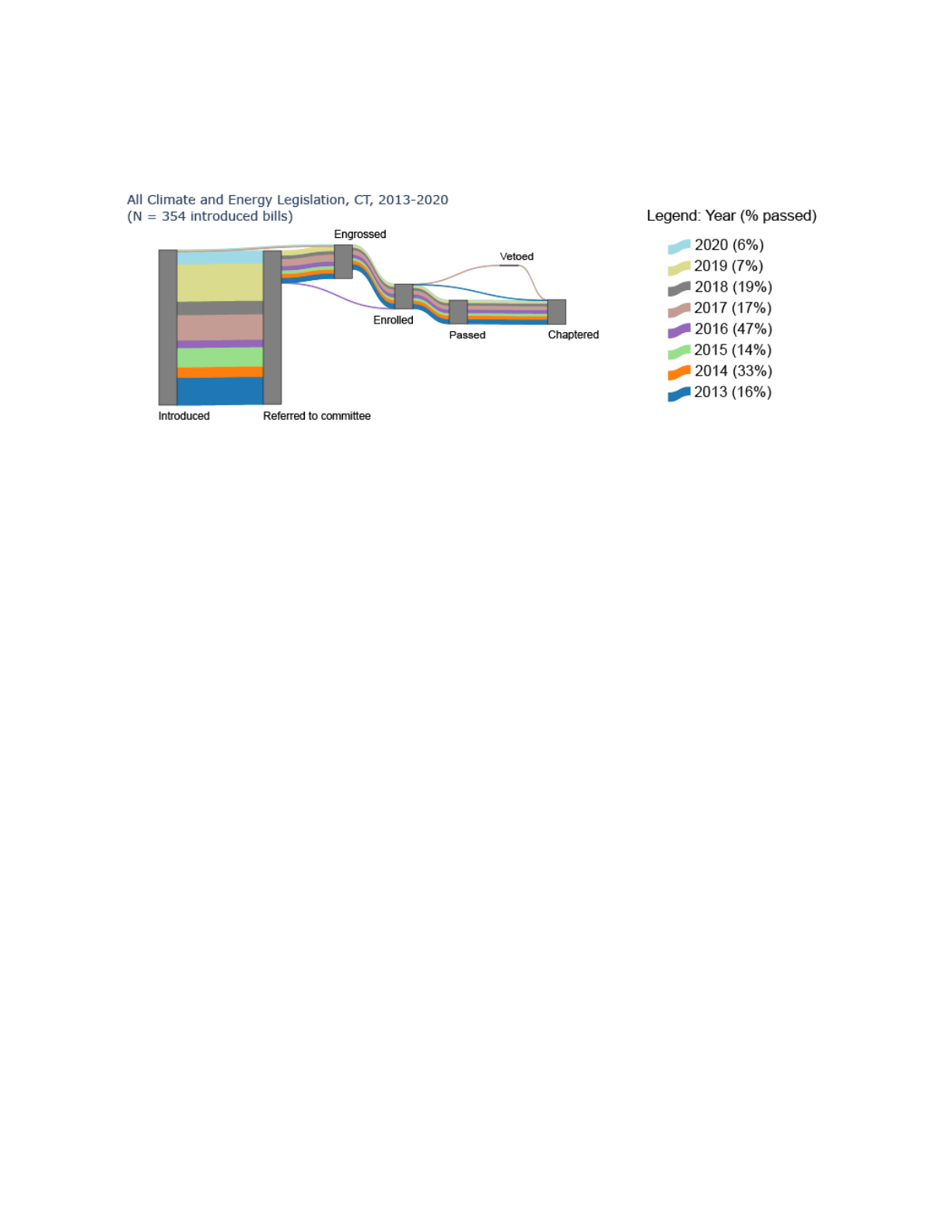

Figure 4: Sankey diagram of climate and clean energy legislation in the Connecticut legislature,

2013-2020. All bills uncovered in keyword search (n = 354).

We find that most climate legislation dies in the original committee in which it was introduced. Of all

354 introduced climate and energy bills, only 78 actually made it out of committee and 56 were

chaptered into law by the Governor (Fig. 4), a survival rate of 16 percent. These statistics emphasize

the importance of influence over committee agendas: while introduced bills are unlikely to pass, the

majority of bills that leave committee are signed into law. On the one hand, this means that when the

full legislature gets to have input on climate bills, they pass those bills. The other way to look at it is

that most legislators don’t get to decide at all about the bulk of energy legislation—it’s been decided

for them before it reaches the floor.

Plotting by year, there are certain years where especially large numbers of bills were introduced, like

2019, when 85 climate and energy-related bills were introduced. But that year was no more

productive in the end than other years; in fact, 2013, 2014 and 2017 each had eight or more bills

signed into law (nine, eight and nine respectively). In terms of “yield” of introduced bills making it

through the process, 2016 was an exceptional year, with nearly half making it through (47%). In six out

of eight years, over 80% of bills were killed, nearly all in the committee where they were introduced. In

2020, just more than 1 in 20 climate and clean energy bills introduced survived (6%).

Research Report: Who’s Influencing Connecticut Climate and Clean Energy Politics? Five Questions // 23

Question 5: What arguments are those

testifying against climate action using?

We reviewed and summarized 263 pieces of written testimony submitted in opposition to 48 priority

climate bills for the years 2013-2020. Not one directly disputed the reality of climate change, and many

expressed their sector’s great concern about environmental issues.

34

But the majority of opposition

testimony downplayed climate change and the efforts being made in the state, and the particular bills

being discussed.

35

Rather than attacking climate science, testimony in the Connecticut legislature sought

to delay or stop the passage of individual climate and clean energy bills. We identified nine discourses

frequently utilized in opposing priority climate legislation, as described below.

Argument 1: Natural gas is essential for Connecticut

Fossil fuel, utility, and labor groups all argued that Connecticut needs a consistent or increasing supply of

natural gas to meet its needs for emissions reduction, energy security, lower energy costs, and

employment.

Over several legislative sessions, Steve Guveyan, local lobbyist for the American Petroleum Institute

(whose national annual budget is over $240 million

36

), argued that the state needs "natural gas---an

abundant, low-carbon, low-greenhouse gas emitting, easily-transported, domestically-produced fuel" (2019

testimony against HB-6242). He and others pointed to emissions being lower thanks to the transition from

coal and oil-generating power plants to gas, that methane leaks are being adequately addressed, and that

pipelines create jobs. His 2014 testimony against SB-237 similarly argued that "Increased use of natural

gas [...] is environmentally beneficial. It will reduce sulfur, PM and mercury emissions, and reduce

greenhouse gas emissions by 30% compared to oil and 45% compared to coal. [...] the country needs an

all-out, all-of-the-above energy strategy that develops every available source of American energy" (2014

SB-237). In response to a 2020 bill, HB-5350, designed to make expansion of natural gas service more

difficult, Patrick McDonnell of Avangrid argued that “Without a comprehensive plan to decarbonize our

electric grid in concert with switching to electrifying our transportation and heating sources, we run the

risk of relying on even dirtier oil fired generation plants to meet our electricity need.”

36

ProPublica. IRS 990 Form for 2018. American Petroleum Institute. Accessed 9 June 2021.

35

Several cited the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change to argue that the U.S. shouldn’t act aggressively on climate

change: The “(IPCC) Assessment Report claims that even if the U.S. as a whole stopped emitting all carbon dioxide

emissions immediately, the ultimate impact on projected global temperature rise would be a reduction of only about 0.08°C

by the year 2050. China and India will dominate global carbon dioxide emissions for the next century, and there’s little the

U.S., let alone Connecticut can do, to change this.” This 2020 testimony, from Christian Herb of the Connecticut Energy

Marketers Association (CEMA) against a Green New Deal bill SB-354, reflects the position they lay out on their website,

asking member oil heat delivery companies to support “our lobbying, consumer outreach, and PR efforts” against the state’s

“diabolical” climate planning.“ From CEMA. 2021. Industry Defense Fund. Accessed 9 June 2021.

34

Three organizations testified against another bill in 2018 (SB-345) that would have included climate change education in

state minimum standards. Remarkably, the Senior Counsel of the Connecticut Business and Industry Association Eric

Brown testified against the use of the words “climate change education,” pushing instead "(line 19) to replace “climate

change” with “earth systems, including earth and human activity”. The Connecticut Association of Schools and the

Connecticut Conference of Municipalities argued that it was an unfunded mandate and would “only decrease the already

minimal amount of time educators have to work with their students on the core curriculum” (Hamzy, Donna, Advocacy

Manager).

Research Report: Who’s Influencing Connecticut Climate and Clean Energy Politics? Five Questions // 24

Eric Brown, Senior Counsel of the powerful Connecticut Business and Industry Association, has been a

frequent voice at the Capitol against climate and clean energy legislation. In 2019 he argued against limits

on expanding pipelines to the region: "Connecticut and New England will be highly dependent on natural

gas for decades to come. Expanding our access to plentiful, nearby quantities of natural gas would yield

economic and environmental benefits for our state and our ratepayers. It is disconcerting to us that the

state continues to make Connecticut a higher energy cost state to achieve greenhouse gas reduction

goals, while at the same time considering legislation that would eliminate a significant opportunity to

make Connecticut a more competitive, less expensive and cleaner energy state" (2019 HB-6242). In these

ways, natural gas is presented as the bedrock of the Connecticut economy and way of life.

Opponents frequently cited the reliability of energy as a reason to not change the status quo. One bill,

2018’s SB-332, included changes in the state’s Department of Energy and Environmental Protection

(DEEP)’s ability to override proposals on pipeline capacity. Gas and electricity utility Eversource’s Vincent

Pace testified against the change, citing a 2018 review of the 2016 cold snap and how gas shortages were

averted (2018 SB-332). Robert Klee, Commissioner of the DEEP, argued that "it is short-sighted to

eliminate this authority, as the underlying issues of natural gas infrastructure constraints, price volatility,

and potential grid reliability impacts persist" (2018 SB-332). The legislation limiting new natural gas

pipelines through the state was opposed by UIL Holdings, which became part of the Avangrid utility: "We

are opposed to House Bill 6242 because it will negatively impact our ability to provide our customers

reliable natural gas service" (2019 HB-6242).

Industry and some labor groups cited social and environmental reasons to support building pipelines. Ted

Grabowski of the Connecticut Laborers District Council argued in 2018 against SB-332 saying that "Our

working men and women who have worked on pipelines [...] take their work very seriously" and that

limiting gas would hurt the state’s economy.

Argument 2: Climate legislation will disproportionately hurt low-income

residents

One of the most frequent arguments being leveled against renewable energy, energy efficiency, and limits

on fossil fuels is that they will exacerbate inequality. For example, the American Petroleum Institute in

2013 came out against HB-6360, saying that "Passing the bill...means you support moving needlessly

from a lower priced fuel [heating oil] to a higher-priced fuel [ultra-low sulphur diesel], one that will impact

every low-income and middle-class family that uses home heating oil." Eversource’s Stephen Gibelli came

out against distributed electricity generation bill SB-928 in 2015, citing “concerns about the cost impact

that many of these new initiatives have on our customers.” CBIA’s Eric Brown made a similar argument on

the same bill, saying that “virtually all the costs and risks associated with such projects on

non-participating ratepayers – who would not even get the benefit of Class 1 energy generated under such

a system being counted towards meeting Connecticut’s highly aggressive and expensive Renewable

Portfolio Standard”. Avangrid’s precursor UIL’s Roddy Diotalevi saw the “virtual net metering” proposal in

2014 HB5412 as a “taking,” "The EDC’s system cannot and should not be commandeered, without

compensation, for the benefit of the Class I renewable energy source."

37

37

2014 HB-05412 Roddy Diotalevi - UIL Holdings Corporation Testimony

Research Report: Who’s Influencing Connecticut Climate and Clean Energy Politics? Five Questions // 25

The Connecticut Chapter of the American Planning Association admits that climate action is needed, but

raises the spectre of NIMBYism and elitism: "while calling it an "environmentally-friendly" decision, many

municipalities will use this as a way to raise the barriers to entry for middle- and lower-income residents in

already deeply unaffordable communities."

38

Sarah Faye Pierce, Government Relations Director for the

Association of the Home Appliance Manufacturers, argued similarly against efficiency standards for

consumer electronics (2019 HB-7151), ”Although AHAM understands the bill’s intent to save energy, HB

7151 has a number of problems relating to home appliances that need to be addressed, not the least of

which are health concerns for those with asthma or allergies [...] and the products’ availability to lower

income and disadvantaged populations."

The argument is common in the real estate sector. In 2020 in response to the Green New Deal bill SB-354,

Jim Perras of the Home Builders & Remodelers Association of Connecticut argued that the "Passage of

this provision will only drive up housing costs further exacerbating the trend of outward migration that

Connecticut is currently experiencing." He concluded "if passed, HB 354 would likely increase the cost of

energy and its implementation would tax state agencies that are already overburden, causing further

construction delays and bureaucratic inefficiencies thereby increasing the already high costs of housing in

Connecticut." That same year, he argued against a bill requiring information about past energy use be

available to home shoppers (SB-177). "As home builders, it is important to our members that prospective

buyers of new construction can sell their existing homes with as few obstructions as possible. In addition,

historical energy consumption data is not necessarily reflective of the energy efficiency of a home." Such

home energy labeling, he argued, "unfairly disadvantag[es] larger families when selling their homes. In

addition, owners of residential rental properties have no control over energy use by their tenants and could

experience similar disadvantages." Similarly, the Connecticut Realtors association opposed requirements

that condominiums have electric vehicle parking spaces and chargers. "The proposal is overly broad,

highly restrictive and provides rights to one user over the rights of all in the Condominium Association

(“Association”). It seeks to obstruct an Association’s ability to determine how to allocate limited common

and parking areas." (2020 HB-5226). Similar equity arguments arise in critiques of the carbon tax.

Argument 3: Carbon pricing is just another tax

Carbon fee and dividend legislation was introduced in Connecticut multiple years in our study, and a

different set of actors came out to oppose it than the usual professional lobbyists for business groups

seen on other issues. Rather, 58 individuals sent one or two sentence emails that are included in state

archives of written testimony; nearly all simply say the state is taxing too much and that spending should

be cut instead. Many point to the pain falling on retired people and modest income residents, especially

those who have to drive long distances for work.

"The unquenchable thirst of the Democratic leadership in Hartford to tax and spend every hard earned

dollar the overtaxed people of Connecticut sends them has got to END!" said Mark Vaghi, an individual not

claiming any affiliation. Suzanne Spinelli expanded: "I understand the need for clean air. Yep, I sure do,

however why are all these ideas funded on the backs of the few middle class individuals that are still in the

state? I drive for a living. [...] How is any kind of a 'carbon' tax going to help me, one of the few that [are] left

in this state that are pulling the wagon? That's right, it won't. This is just another ploy for a money-grab on

the backs of people like me, the few, the proud, the five residents (it feels like) that have jobs and are

38

2020 HB-05008 CT Chapter-American Planning Association Testimony

Research Report: Who’s Influencing Connecticut Climate and Clean Energy Politics? Five Questions // 26

paying taxes to fund your excessive programs. [...] Until then people like me will just get squashed until we

decide to give up, and either leave, or become one of the welfare takers. Is that what you want?"

These brief and angry emails appear to be the result of mobilization by libertarian groups in the state, as

was clear when one respondent included “Put Bill 5363 in the subject line” in their email.

39

Grover Norquist,

founder and leader of Americans for Tax Reform, a national group opposed to tax increases, submitted

written testimony of his own to attack the bill, saying that "Enactment of a carbon tax, a regressive tax that

would disproportionately harm low and middle-income households, would exacerbate the exodus of

individuals, families, and employers from the Nutmeg State." In other written testimony, the libertarian

Yankee Institute for Public Policy argued against HB-5363 in 2018 that "From a jobs and economic

perspective, imposing a tax on carbon emissions would be a terrible mistake. This proposal [...] burdens

both Connecticut’s economy overall, as well as disproportionately harming the poorest among us."

"[S]imply put, no dividend paid out to either businesses or individuals can possibly offset the economic

harm of this proposal." Lobbying materials still on the Energy Marketers group website consistently only

discuss the fee side of the legislation, not the dividends that it called for to be distributed to each

household and business in the state.

40

Argument 4: Connecticut is too small to matter

Twelve heating oil delivery companies sent modest adjustments of a form letter making a series of points

about how much the carbon tax would cost residents and firms (and not mentioning the dividend). They

also argued that Connecticut is small and other places are emitting more, even than the U.S.: "The tax is a

"feel good" tax that won't affect climate change. According to a U.S. News & World Report article, even if

the U.S. completely stopped emitting all CO2, it would reduce world temperatures by only 0.08 degrees C

by the year 2050." (2018 HB-05363 Mercede, Erin Testimony). Shawn Driscoll of Global Partners LP, a large

network of oil and gasoline distributors in the Northeast, simply argued that "[U]ntil the rest of the world

changes its energy consumption and carbon dioxide emissions, there is little upside to putting the

Connecticut economy at such as a disadvantage.” (2018 HB-05363)

In criticizing the carbon pricing bill in 2018 (HB-5363), Senior Counsel Eric Brown of CBIA utilized a series

of climate skeptics arguments. “To provide some context, the climate is changing. Human activity is may

well be [sic] impacting the pace of that change. Even if one believes that impact is significant,

Connecticut’s contribution to such impact is indisputably negligible. DEEP’s [the state’s environment

agency] own studies show that if we stopped generating and using electricity entirely; if every car, truck

and bus were banned in Connecticut; if we shut down every manufacturing facility, every restaurant, every

doctors office, hardware store and flower shop; if we stopped building helicopters, jet engines and

submarines – in short – if we transported Connecticut (as well as Massachusetts and Rhode Island for

that matter) back to a 15th century economy – Connecticut would still not meet EPA’s current air pollution

standards because of pollution we import from upwind states. It is surely even more true that doing so

would have no measurable impact on global climate trends."

41

In short, we should not adopt the policy

because Connecticut is too small to matter.

41

2018 HB-5363 Brown, Eric, Senior Counsel-Connecticut Business and Industry Association Testimony

40

For example see CEMA. n.d. A Problematic Truth. https://www.ctema.com/a-problematic-truth/ Accessed 9 June 2021.

39

2018 HB-05363 Dwyer, Jim Testimony

Research Report: Who’s Influencing Connecticut Climate and Clean Energy Politics? Five Questions // 27

Argument 5: Renewables and EV bills are unrealistic and unfair

Renewables were sometimes portrayed as fanciful and unrealistic. "While desirable in theory, an all-electric

economy cannot be achieved in practice,” testified Bill Chu, Vice President of the Connecticut Energy

Marketers Association, in opposition to a 2020 Green New Deal bill. “The amount of land or sea area that

solar or wind farms would consume would be too great. The materials such farms require are very

carbon-intensive to produce, and the huge volume of solar panels and wind farm blades will result in a

massive waste disposal problem.” He continued that the state “would also be at a severe disadvantage at

competing with the rest of the country, and the world, for electric vehicles to achieve the goal of an

all-electric transportation sector, as such EVs will be in short supply due to the limitation on rare minerals

and elements they require. And even when these are secured, the disposal of used EV batteries poses a

hazardous waste risk."

Dozens of car dealers submitted written testimony against legislation to allow Tesla Corporation to sell its

electric vehicles without a dealership in the state (2017 SB-973). Local dealers repeatedly said that

dealerships support communities, create jobs, give to local charities, care for their customers, and that

this bill would open the door for Chinese and Indian electric cars to be sold in the state. Further, they

responded to a claim made by Tesla in previous sessions.

42

The Connecticut River Valley Chamber of

Commerce’s Ellen Dombrowski supported that position in 2017 testimony against HB-7097: "Among our

members are several automobile retailers, significant taxpayers, who oppose this measure. The Chamber

strongly opposes H.B. 7097 as its passage would seriously jeopardize the successful, long-standing

franchise model. The passage of such a measure would impact over 14,000 Connecticut employees in the

automobile sector as it currently exists.”

43

These efforts make changing the status quo a daunting task. A bill in 2015 sought to require EV chargers

for any parking lots with more than 100 spaces (2015 HB-7009). The Connecticut Conference of

Municipalities argued that doing so “could usurp local officials’ critical feedback,” and could have a fiscal